Ipatiev House, 1918. Citizen Nicholas Alexandrovich Romanov1 along with his family and their remaining servants were imprisoned in Yekaterinburg, Russia. In the early hours of the morning of July 17, they were escorted into a dingy half-cellar room. Hours later, their bullet-ridden, bayoneted, bludgeoned corpses were desperately discarded; some buried, some burned. Bolshevik revolutionaries executed the last tsar of Russia and his family on orders from the Ural Regional Soviet for their supposed continuing attack on Soviet Russia. Over a century has passed since the fall of the Romanov dynasty. The romanticisation of the family, especially that of Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna, lives on. How did we get from that bloody execution to the glamorous dream of displaced royalty?

From Fox’s 1997 Anastasia to many other low-budget knockoff versions (my personal childhood favourite The Secret of Anastasia), at the turn of the 20th century, animation studios had young girls dreaming of being discovered as a lost princess. It appears to be a common experience of girlhood to have developed an obsession with Anastasia and then the horror that follows upon discovering the truth of the real-life Anastasia. Fox’s Anastasia is the pulsing heart keeping the pop culture romanticisation of Anastasia and the Romanovs alive. TikToks and Instagram reels showing clips from the film, featuring music from the film/musical play production, revealing historical facts, all racking up millions of likes and views. We are wired to love a rags-to-riches story; we too fancied up dreams of being elevated from our mundane reality, just like ‘Anya’ the amnesia-suffering orphan who is plucked from the streets of Soviet Russia and discovers her true royal identity, reuniting with her beloved grandmother, falling in love, and defeating the wicked wizard Rasputin (Who said anything about historical accuracy?).

The allure of Anastasia is a string that can be traced throughout history. Fox’s Anastasia shares a similar plot with the 1956 film of the same name, based on Marcelle Maurette’s 1952 play. The plot goes as follows: A former Russian general grooms Anna Anderson, a destitute amnesiac, into becoming the lost Grand Duchess Anastasia in order to obtain £10 million inheritance from the Bank of England. Both Anna herself and the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (Anastasia’s paternal grandmother) truly believe Anna to be Anastasia. However, as Anna has fallen in love with the General Bounine, the Dowager Empress allows them to run away instead of announcing the truth. Very romantic indeed. The history is much less so.

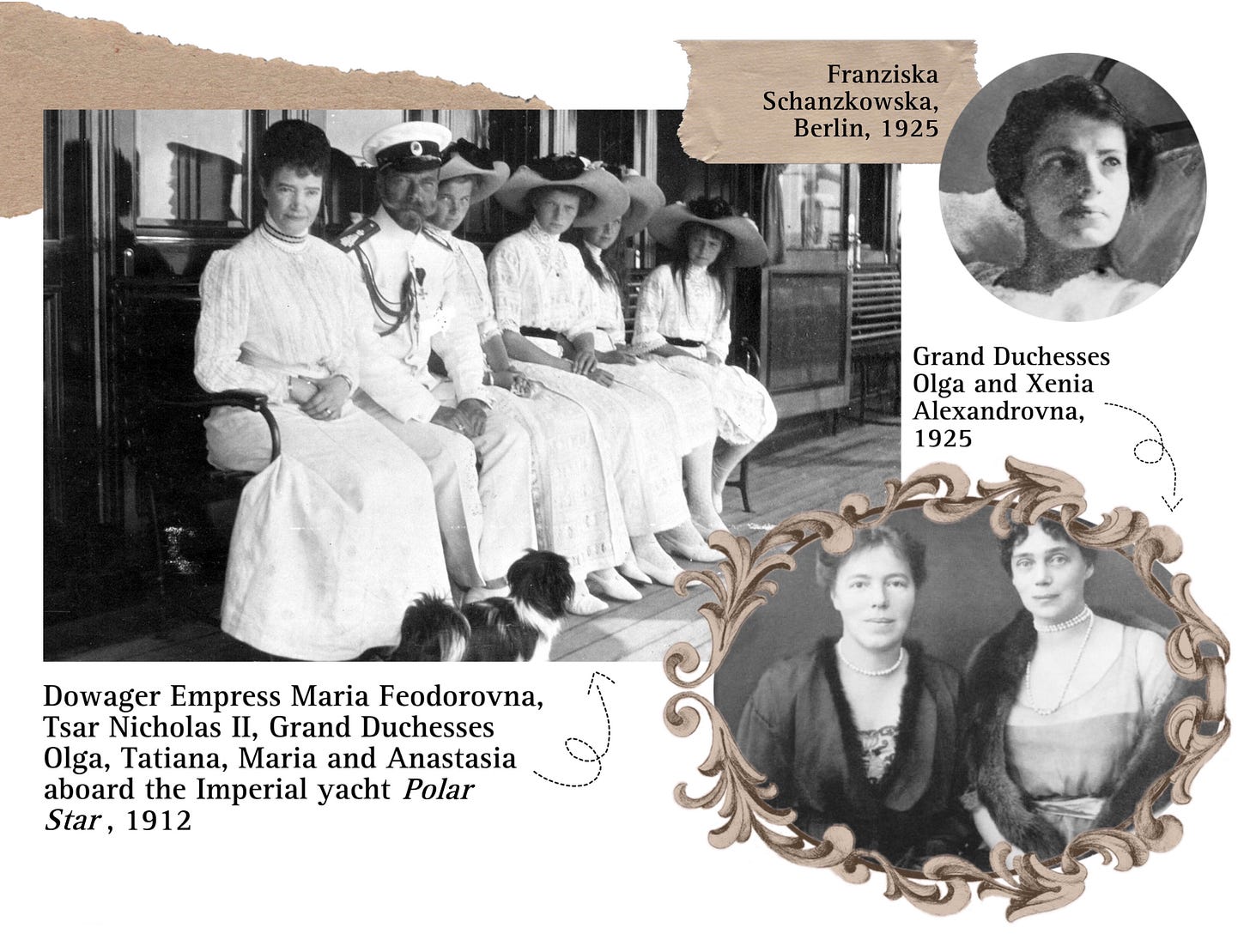

The story is based on Franziska Schanzkowska aka Anna Anderson, a mentally ill Polish factory worker who was institutionalised after attempting suicide in Berlin in 1920. By 1922, she was claiming to be a Russian Grand Duchess, first as Tatiana (Anastasia’s sister), then as Anastasia. Visits followed from acquaintances, friends and family, all seeking to discover whether this woman was telling the truth or if she was an imposter. She was known by many aliases, the most popular being ‘Anna Anderson’.

It is easy to forget that although the early 20th century fall of the Romanov dynasty seems worlds away, there were still survivors of the end of the empire that lived on, most notably the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, who plays an important role in the romance of Anastasia. Princess Dagmar of Denmark, wife of Alexander III and mother of Nicholas II. In 1919, in what certainly may have been her last chance of escape, Maria reluctantly left Russia on HMS Marlborough to the singing of God Save the Tsar. She stood, dressed in black, waving goodbye to Russia until she went out of sight. At the age of 71, she began her life of exile. It’s important to remember that the true details of her family’s execution were not known until many decades later and, although most people accepted that at least Nicholas had been murdered, Maria steadfastly told people that her beloved son and his family were alive. The Dowager Empress vehemently declared Anna Anderson to be an imposter and insistently attempted to steer her daughter Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna from feeding into the publicity, the opinion reinforced by her other daughter Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna. The Dowager Empress had upheld the dignity of the fallen house of Romanov in exile and did not welcome discussion of frauds. Ultimately, for Maria to decide Anna was Anastasia would mean for her to believe that her family had been executed, which she refused to do until her dying day, at least outwardly. She died at the age of 80 in her native country of Denmark in 1928. As a symbol of Imperial Russia and the head of the Romanovs, a few decades later she would fictionally reprise her role of the adored grandmother deciding the fate of whether her granddaughter was still alive. When we put history into perspective, it is interesting to note that the aforementioned play and film of Anastasia were made within the lifetimes of Anastasia’s aunts, the Grand Duchesses Olga and Xenia, who both lived until 1960.

DNA testing later proved the disbelievers to be correct, as Anna Anderson was confirmed to be Franziska Schanzkowska. In 1991, the bodies of five family members were exhumed. The remains of most of the family and their servants were found by two amateurs, Avdonin and Ryabov in 1979, a secret kept until the collapse of the Soviet Union. The romance of a lost princess was thoroughly shattered in 2007 when the two remaining bodies of Anastasia’s siblings, Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich and his sister Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna (at times believed to be Anastasia’s remains) were found. In the spirit of the final lines of the 1950s character version of the Dowager Empress: “The play is over. Go home.”

And so the curtain falls on the romance of Anastasia or one of the Grand Duchesses miraculously surviving a brutal execution. Here enters the morbid romance of a princess murdered. Anastasia’s story is now transformed from the more dignified mystique that captured the interest of the 20th century. Although distressing for the Romanovs in exile, the fascination with a surviving Anastasia was a genuinely placed intrigue before her remains were discovered. Truth now being known, it gave way to a kind of gruesome magnetism. Another facet of the romance, born from a culture that loves true crime, a strange fixation on horrible murders. Anastasia’s true story stands in juxtaposition to the magic that those animation studios painted for us. The contrast is jarring: a Cinderella tale with princess dresses, dazzling ballrooms and oh-so-romantic Paris to that horrendous room in Ipatiev House. The Yurovsky Note is an account of the event filed by Yakov Mikhailovich Yurovsky, commander of the guard at Ipatiev House and chief executioner of the family. He recalls a room full of gun smoke, bullets ricocheting, screaming girls that they just couldn’t seem to kill due to their clothes being laced with hidden jewels, and many more sickening details that I will not dwell on. There’s something about that room that seems to get stripped of its humanity; it’s hard to truly comprehend the horror.

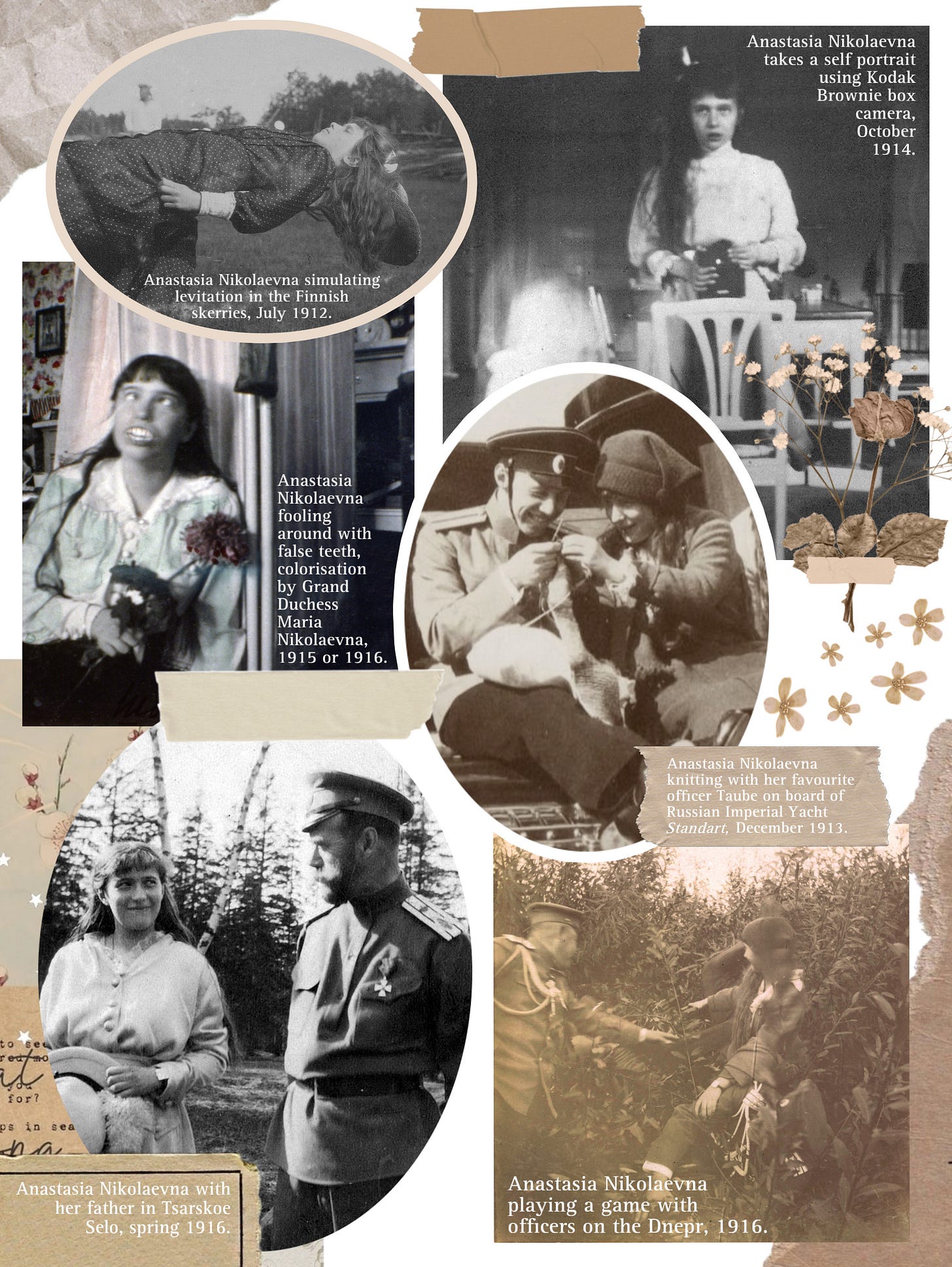

Yet, somewhere in between all the romance — dreamy or dreadful — lies the real Anastasia. Called ‘Shvipsik’ (little mischief) by her family, Anastasia is described as being hilarious, rebellious, fearless, a force of nature with a fierce love for life who could dispel any gloom. Despite burnings of certain personal diaries and letters, we still have many wonderful accounts of the Grand Duchess. One of the most touching and valuable portraits of Anastasia comes from Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna’s recollection of her favourite niece, thankfully written down by Ian Vorres in his biography The Last Grand Duchess: Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna. Here are some excerpts that best summarise Anastasia:

“My favorite god-daughter she was indeed! I liked her fearlessness. She never whimpered or cried, even when hurt. She was a fearful tomboy… And what a bundle of mischief!”

“But she was a Shvipsik indeed,” the Grand Duchess went on. “As she grew older, she developed a gift for mimicry… That art of Anastasia's was not really encouraged, but oh the fun we had… Very naughty of Anastasia, but she was certainly brilliant at it!”

“…Why, I can still hear her laughter rippling all over the room. Dancing, music, games — she threw herself wholeheartedly into them all…”

“…She so wanted to come to grips with life. I know there were many things that troubled her. She hated the Cossack escort always accompanying their outings and so on, but none of it marred her gaiety. That is how I remember her — brimming with life and mischief and laughing so often — sometimes for no reason at all, which is the best kind of laughter. The child was the gayest Romanov of her generation and she had a heart of gold.”

There are so many delightful memories of Anastasia. Also, thanks to the Romanov’s love of photography, we have thousands of photos both of and taken by Anastasia which reflect her vivaciousness. I’ve included some of my favourites.

On 15 August 2000, the Russian Orthodox Church announced the glorification of Nicholas II and his immediate family for their meekness during Bolshevik imprisonment and execution. The family had previously been canonised in 1981 by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad as Holy Martyrs (not without controversy). Martyrs are killed for their faith, whereas passion bearers are those who face their death in a Christ-like manner (all martyrs are passion bearers, not all passion bearers are martyrs). In popular veneration, the family is still most often referred to as martyrs. Depicted in her sainthood, there are many beautiful icons of Anastasia and her family.

Over a century later, the short but vivid life of Anastasia and the broader tragedy of the Romanovs still manage to hold our interest. Without the romance of the tragic ending of an empire, the imaginative rumours of a miraculous survival, and ultimately a bitter reality, would Anastasia and her family ever hold the popularity they have today? Most likely, they would be lost in the sea of royalty of the past. One of my favourite books is Four Sisters: The Lost Lives of the Romanov Grand Duchesses by Helen Rappaport. The daughters of Nicholas II, Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia, referred to by the collective ‘OTMA’, were often overlooked by historians, mentioned as a unit in passing. Rappaport paints an intimate picture of the lives of the Grand Duchesses. It is touching and informative and certainly does them justice. One of my favourite memories of Anastasia is told here in an excerpt written by Rappaport from the account of the children’s tutor Sydney Gibbes (who voluntarily accompanied the family into exile in Tobolsk) as he remembers a particular play put on by ‘The Little Pair’:

The biggest hit was Packing Up - ‘a very vulgar but also very funny farce by Harry Grattan’ in which Anastasia played the male lead, Mr Chugwater, and Maria his wife. During her energetic performance on 4 February the dressing gown Anastasia was wearing flew up, exposing her sturdy legs encased in her father's Jaeger long johns. Everyone ‘collapsed in uncontrolled laughter’ - even Alexandra, who rarely laughed out loud. It was, remembered Gibbes, ‘the last heartily unrestrained laughter the Empress ever enjoyed’. The play had been so ‘awfully amusing & really well and funnily given’ in Alexandra's estimation, that a repeat performance was demanded.

I have also encountered many spaces online dedicated to a genuine love of these historical figures. The girls lived a very isolated life, surprisingly simple despite their royalty, sorrowful at times but thoroughly full of love. They couldn’t have possibly known, as they huddled together in Ipatiev House, that a century after their deaths people would still be reading their letters, looking at their photographs, learning about their lives and venerating them as saints. Anyone with a heart would feel the utmost pity and heartbreak for those innocent children who undeservedly met such a cruel fate.

There is so much more to Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna than her death and the fictionalised character in popular culture, one that I would encourage anyone to discover for themselves, alongside that of her siblings. But aside from the excruciating end and continued grief of that fateful execution, the romanticisation of Anastasia and her family ultimately gives way to a sincere interest and even times a heartfelt love for a girl who had enough personality to transcend a century.

Abridged Letter from Anastasia to her sister Maria.

24 April/7 May, 1918. Tobolsk.

(Translation from Helen Azar, Maria and Anastasia: The Youngest Romanov Grand Duchesses In Their Own Words: Letters, Diaries, Postcards)

Indeed He Has Risen! My good Mashka Darling. We were so terribly happy to get the news [from you] and shared our impressions! I apologize for writing crookedly on the paper, but this is due to my foolishness… We are always with you in our thoughts, dear ones… We took pictures. I hope they come out. I continue to draw, not too badly they say, so it's very pleasant. We swung on the swings, and when I fell it was such a wonderful fall... Yes, indeedy! I told the sisters about this so many times yesterday, that they got tired of hearing about it, but I could tell it again and again, although there is no one left to tell... I very much apologize [that I] forgot to send good wishes to all you dear ones for the holiday; I kiss you all not thrice but lots of times… Such a laugh from the journey... I would need to tell you this in person, and laugh. We just had tea. [Alexei] is with us and we just devoured so many Paskas that I plan to burst. When we sing amongst ourselves, it comes out badly because we need a fourth voice, but you are not here and therefore we make terribly witty comments about this... Well, it looks like I have written enough foolishness. Right now I will write some more, and then I will read a bit, [it is] so nice to have free time. Goodbye for now. I wish you all the best, happiness, and all good things. We constantly pray for you and think [of you], may the Lord help. May Christ be with you, precious ones. I embrace you all very tightly... and kiss you...

Bibliography:

Little Mother of Russia: A Biography of Empress Marie Feodorvovna, Coryne Hall

The Last Tsar: The Life and Death of Nicholas II, Edvard Radzinsky

The Last Grand Duchess: Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, Ian Vorres

Four Sisters: The Lost Lives of the Romanov Grand Duchesses, Helen Rappaport

Maria and Anastasia: The Youngest Romanov Grand Duchesses In Their Own Words: Letters, Diaries, Postcards, Helen Azar

A note on names and titles: I have used the titles Emperor and Empress, Tsar and Tsaritsa interchangeably throughout. I have also used patronymic names, which may be unfamiliar to some. They derive from the father’s first name with a suffix that indicates “son of” or “daughter of”, for example Nikolaevich and Nikolaevna from the name Nikolai. I have opted to use the more popular romanisation of names such as Nicholas Alexandrovich.